.png)

.png)

When I was 12 years old, I realized I was queer. I had NO verbiage for it, because it was 2012 and I was 12, and smooth-brained, and from a mildly conservative-religious suburb in the northeast. So, I told my friends that I was “gender-fluid”. What I meant was that I was “bi” or that I liked both men and women, and in my head that meant I was “fluid” about liking both genders 💀. My best friend and I still cackle about it to this day. The realization came so naturally to me, that I didn’t really think to investigate it any further. It wasn’t until I was 16 years old that I stumbled across the phrase “bisexual” somewhere on the internet, probably Tumblr. And from that moment on, I was introduced into the sprawling world of queer culture via online spaces. I finally had the verbiage to talk about my identity. I stumbled across memes that poked fun at my lived experiences and inner thoughts, specific to my sexuality. For the first time, I also started to find discourse online that criticizes bisexuals.

The internet is a double-edged sword (well, honestly, probably a multi-edged sword but for all intents and purposes of this article we’ll say double). On one hand, you can rely on social media and the internet to discover something new about yourself and find communities that support, uplift, and even reflect that. On the other hand, identities and communities are subject to the same algorithmic gambit that anything on the internet is at risk of: trolls, fetishization, and the dissolution of core features of a community. With Gen Z being the most diverse generation to ever exist (only 52% of Gen Zs are white, ~28% of Gen Zs identify as LGBTQIA+, etc.), online communities have become an integral part of marginalized communities and their shared perception of identity. But it hasn’t come without its costs. We asked our Koi Pond members who identify with marginalized communities like BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, disabled, etc. how their identity lives out, and is impacted by, being a part of online communities, and what role brands can play in actually supporting the communities they purport to support.

From Fandom to Friendship

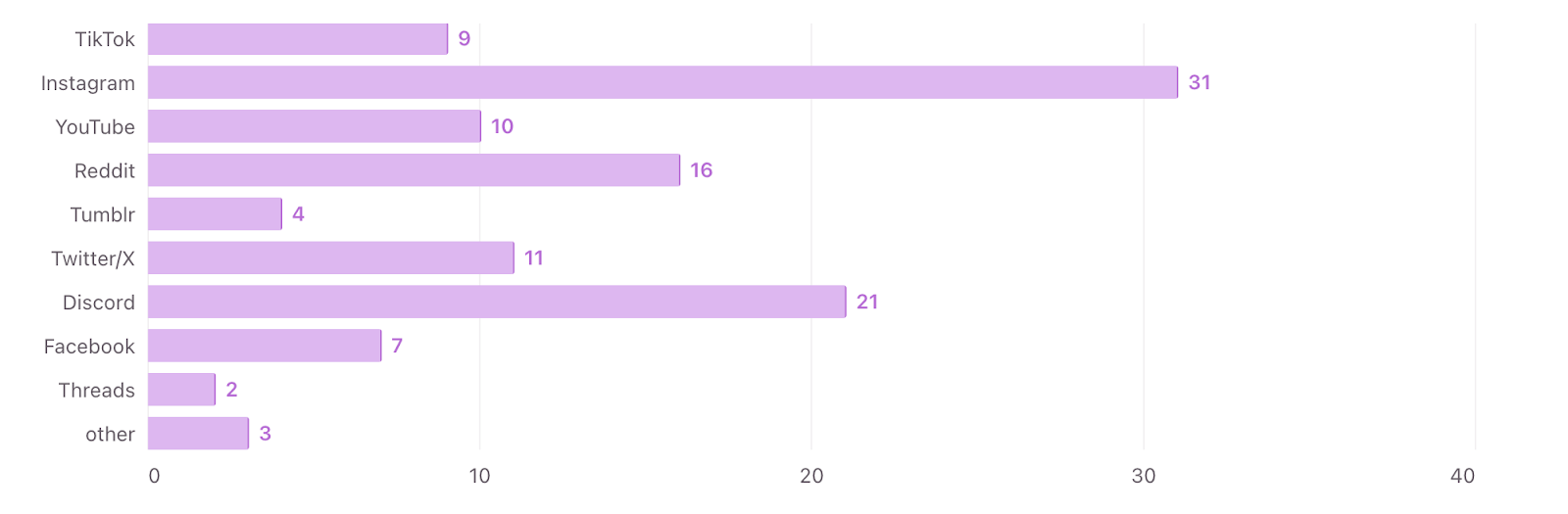

Interestingly, a major starting point for our respondents finding their current online communities is the world of online fandom. Of the 62.5% of survey respondents who have found camaraderie within their communities online, about 20% of them cite fandom as being a point of entry to their online communities as a whole. Which honestly makes so much sense, because in my personal experience being a part of various anime fandoms, you’ll find some of the most welcoming and diverse folks on the internet in those spaces. I was majorly introduced to the queer community through anime fandoms. Platforms like Discord and Reddit were ranked second and third as being the most used platforms for connecting with community members. Despite short-form video dominance, communities yearn for textual and oratorical connection even across the interwebs. Instagram still took the #1 spot though (can’t win ‘em all).

A Safe Haven

The beautiful part of online communities, particularly for marginalized folks, is clear when you take into consideration how life changing (and potentially lifesaving) access to information can be. Plenty of respondents cited the internet as giving them the vocabulary to describe who they are, for introducing them to histories and knowledge they would’ve otherwise never been introduced to, and for putting creators on their algorithms who reflected their identity and could share important resources.

“When I was younger I knew I was queer somehow, but none of the labels really fit. My gay friends and I kind of understood that I definitely wasn't straight and cis but we didn't really have a word that fit what I was. Online queer communities really helped me find a word to explain how I felt…”

“I’ve followed individuals with the same religion as mine, and they made me feel seen and not ‘crazy’ for being in a minority religion.”

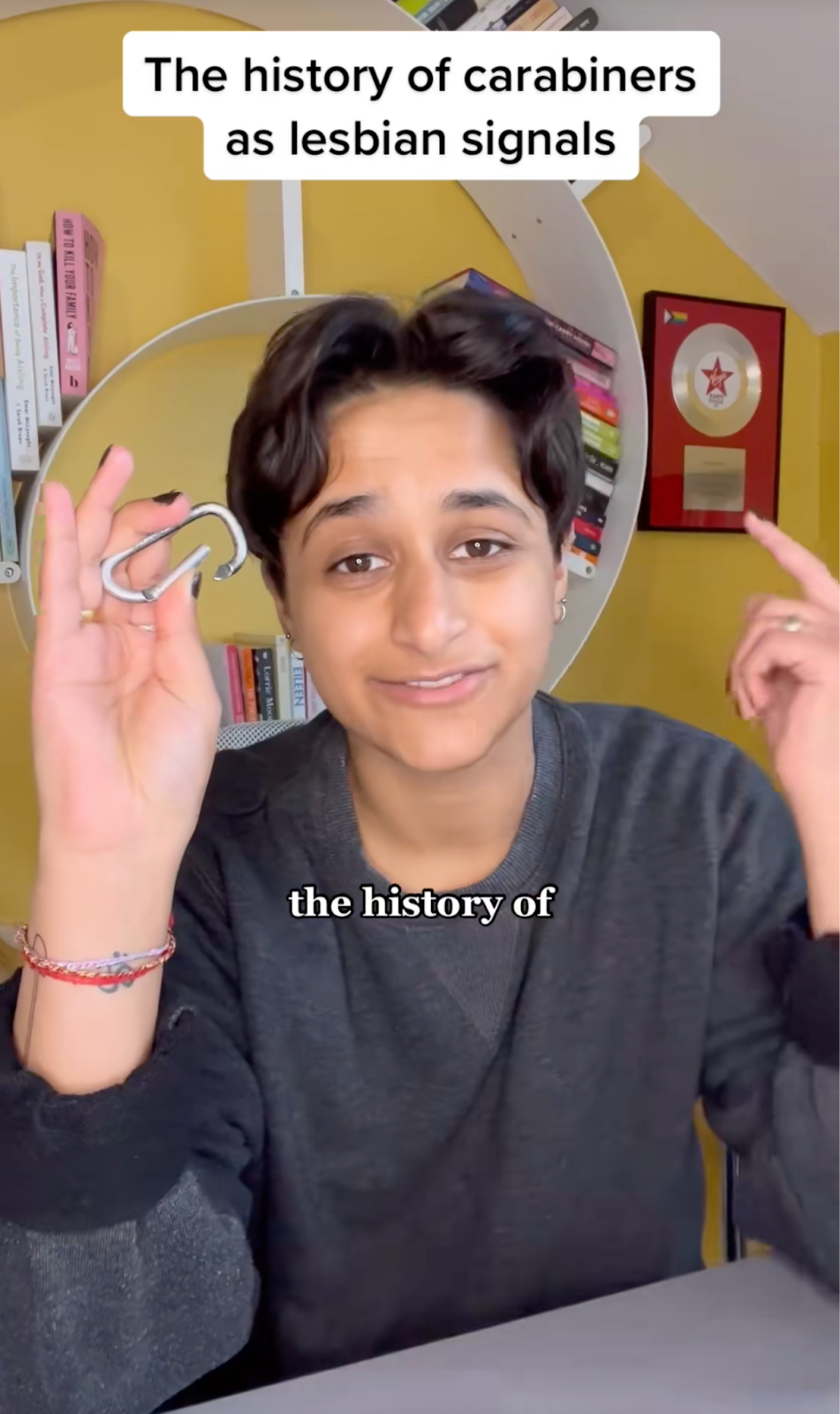

For marginalized communities, the internet enables their identity to not just be discovered, but to be shared. In the LGBTQIA+ community, for example, there are plenty of online “stereotypes” that were pointed out online, agreed upon online, and then played out in real life. One example being that queer folks (usually lesbians) wear carabiners on their belt loops. This dual fashion-statement / sexuality identifier is nothing new, and has long been a part of secretly signaling to folks within the lesbian community that you were part of them. But, the rise of social media popularized this knowledge and made it accessible to “baby gays”, as well as the rest of the world. It is the perfect reflection of how a community unites under common identifiers, styles, and aesthetics offline, which gains traction through the internet, and then actualizes in a way that becomes mainstream and part of the greater cultural fabric in real life.

For marginalized communities, the internet offers a sort of safe haven for discovering and exploring an identity. About a third of respondents said they felt safer talking about their identities online than in person.

Performance Ouroborus

While being able to identify your community online, participate in discourse, align on common values, and develop a shared sense of identity is all fine and great, there’s a downside to it all. The internet has a funny way of making you simultaneously feel in on the joke and an outsider in your own algorithm. So what happens when that “shared sense of identity” starts to become the only way the rest of the world sees your community? Take, for example, the “ABG” subculture of Asian Americans. The ABG or “asian baby girl” stereotype is a stereotype (with a long history of existing offline) that entered the mainstream dialogue on social media in recent years. It categorizes a group of Asian American women by identifying them as girls who have a particular affiliation with rave culture and nightlife, as well as dress and do their makeup a specific way. This stereotype has been criticized in recent years for being, well, a stereotype, and for limiting a cultural group to a specific archetype.

The internet and social media speeds this process up tenfold for marginalized communities, and can negatively impact both outside and inside opinions of a community. Our respondents felt the same way saying that it has made them “compare [their] social interactions more” and that social media has “negatively changed [their] perception of things”.

“People have posted stereotypes about non-binary people that have made me feel a little self-conscious and I make sure I don't emulate those stereotypes in-person”

“Stereotypes used to make me either change myself to fit in better or to disassociate myself with a certain community.”

A Resource, Not The End Game

Online spaces are imperative for marginalized communities, and can be lifesaving resources for some folks. Several respondents say that being a part of their online communities has made them feel less alone in the world. It’s helped to evolve different communities by expanding reach, creating more cultural impact, and garnering more visibility & support for their community.

But it shouldn’t be the end all be all. Social media can also “grow negative feelings, of being ‘the other’ and fuel the wrong type of thoughts at times”. Our survey respondents recognized this and actually voiced their preference (and stressed the importance of) offline time with your community, with one Koi Ponder even saying: “My IRL communities have been hurt because we can go without actually talking since we can just see each others' posts to know what's going on in each others' lives.” Several other responses cited their IRL interactions suffering or atrophying as online interactions have come to replace them.

For now, the increase in accessibility to likeminded folks, access to knowledge and information, and a shared sense of identity far outweighs the negatives for being a part of communities online for marginalized folks.

How Brands Can Support Marginalized Communities IRL & Online

The role that brands can play in all of this is tricky. Gen Zs can sniff out bogus from a mile away. We grew up with corporate pride emerging, shaking, and then crumbling under pressure right before our eyes in the span of a decade; we’re abundantly cautious and speculative of brand-focused inclusion and initiatives. The only way for brands to properly support communities, is by including voices and representation from within the communities that brands are trying to market to and consulting members of the community where necessary. Brands like Ben & Jerry’s were referenced multiple times as a brand worthy of support from marginalized communities: “It doesn’t really need to be a big deal ‘FIRST GAY CHARACTER’ ‘HAPPY PRIDE’ it’s not about social media engagement, it’s about values (like Ben and Jerry’s)”. Ben & Jerry’s has a long history of putting their money where their mouth is, helping to organize protests in support of their mission and values, publicly sharing resources and information regarding various social justice causes, and even starting a foundation to assist grassroots organizations in doing the same.

When asked what it would take for a brand to represent or advocate for their identity, most respondents answered in a way that called for true activism, not just “for a specific month”. Most respondents cited donating to causes related to their communities, hiring creators and voices from within the community to design campaigns, and for campaigns to go beyond surface-level meaning. A lot of folks also stressed that solidarity / activism for marginalized groups does not need to be loud, it just needs to be real. Don’t slap a rainbow on something if you’re not going to support DE&I initiatives. The less corny and in-your-face the campaign is, the more we actually believe you care about the folks you claim to care about.

Most importantly, brands should acknowledge whether or not the campaign they’re employing actually serves the community they’re leveraging. If not, then don’t even bother.

Marginalized communities don’t need brands to step into an already complicated relationship between their identity and the way the world sees it played out online and in person. Instead of adding to the noise, brands should consider meaningful, actionable ways to support marginalized communities through their online and OOH campaigns. The internet is a double-edged sword enough as it is; brands should make sure they’re on the side of the blade that progresses these communities towards care, understanding, and safety.